1. Introduction

Children who grow up in residential childcare represent a particularly vulnerable group of our

society. Their lives are often shaped by adverse childhood experiences, family breakdown, trauma,

and long-term exposure to dysfunctional family systems (Alfandari & Taylor, 2023; Brend, Collin

Vézina, & Daignault, 2025; Daněk, 2024). These children frequently come into residential childcare

from diverse social and cultural backgrounds. Their face persistent challenges related to social

exclusion, educational underachievement, and restricted opportunities for cultural and civic

participation (Bach-Mortensen et al., 2022; Sindi, 2022). We can see that significant educational

inequalities remain despite continued efforts to reform institutional care in Central and Eastern

Europe. Many existing educational interventions in residential childcare are insufficiently tailored to

individual needs, do not fully incorporate modern technologies, and fail to support the development

of essential twenty-first-century competencies adequately. This fact harms children's emotional,

cognitive, and social development (Izzo et al., 2022; Kendrick, 2015).

The educational and social trajectories of children in residential childcare are influenced by a

complex set of factors. Among the most frequently identified barriers that children in residential

childcare face are the low continuity of educational experiences. Another factors are limited support

networks and insufficient coordination between care providers and educational institutions

The article has been submitted for peer review to the international scientific journal Problems of

Education in the 21st Century (ISSN 1822-7864).

(McCafferty, Hayes, & McCormick, 2025). These critical determinants are further compounded by

disparities in access to modern educational resources and contemporary technologies (UNICEF,

2023). Such disparities not only constrain the development of educational and digital competencies

but also risk deepening existing social and educational inequalities.

Residential childcare is not immune to the dynamic transformations shaping contemporary

society. The rapid advancement of modern technologies and sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI)

tools is one of the most significant developments of recent years. Increasingly, AI is discussed as a

promising means of supporting education, not only within the framework of formal schooling but

also in the realm of non-formal, inclusive, and individualised learning (Vieriu & Petrea, 2025;

Luckin et al., 2016). The potential of AI lies especially in its capacity to personalise learning content

and enable adaptive assessment. AI has fostered the development of twenty-first-century

competencies. These are precisely the areas that hold critical importance for residential childcare

settings.

It is essential to acknowledge the limitations and ethical considerations surrounding AI

integration. It is necessary to foster the protection of personal data, the guarantee of equitable

access, and the cultural relevance of educational content (Mainzer & Kahle, 2024; Stárek, 2025).

For these reasons, the benefits and possibilities offered by AI emerged as a cross-cutting theme in

our research, which is situated within a broader framework that integrates cultural, sporting, and

educational activities to promote the inclusive development of children in residential childcare.

Research Problem

There is a marked lack of systematic, methodologically rigorous research on innovative

educational approaches adapted to the specific context of residential care. The present study

addresses an urgent societal and professional priority by examining the potential of integrating

educational, cultural, and sports-based interventions. Those activities are augmented by artificial

intelligence tools, into the holistic development of children and young people in residential

childcare. The use of artificial intelligence as a supportive pedagogical instrument remains

underexplored. This is especially relevant in light of the evolving needs of care-experienced children

and the growing demand for inclusive, future-oriented educational frameworks (Daněk et al., 2023;

Calheiros & Patrício, 2014). National systems of residential childcare differ significantly, because

they are shaped by distinctive policy and cultural contexts (Daněk et al., 2024). Nevertheless,

through sustained cooperation with FICE Czech Republic and FICE International, thematic areas

have been identified that may carry broader transnational relevance.

Research Focus

This study focuses on the educational opportunities that can be developed within residential

childcare through the integration of cultural, sports, and educational activities. Particular attention is

given to the use of artificial intelligence tools in the creation of adaptive learning materials, in

supporting educators, and in the personalisation of the learning process. The research builds on

long-term examination of education in children’s homes and employs an international project

funded by the Visegrad Fund as a model case for testing innovative approaches. The project brought

together participants from the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and a unique group from a Ukrainian

children's home that had been evacuated to Poland due to the war.

Research Aim

The main aim of this study is to identify, describe, and evaluate educational approaches that

can foster personal development, social inclusion, and digital literacy among children in residential

childcare. The study seeks to provide evidence-based foundations for the broader implementation of

innovative methods, including the use of artificial intelligence, within non-formal education in

residential childcare settings.

Research Questions

What educational opportunities arise from the integration of cultural, sports, and educational

activities within residential childcare settings?

What role can artificial intelligence play in supporting inclusive education for children in

residential childcare?

How can these approaches be implemented across diverse cultural and institutional contexts

within the Visegrad Group countries?

Research Methodology

General Background

The present study is rooted in our longstanding scientific and professional interest in the

education and development of children growing up in residential childcare settings. This population

faces significant limitations in access to individualised learning, modern educational technologies,

and inspiring cultural or sports activities. Our long-term research activities have therefore focused

on identifying effective methods that can compensate for these deficits and better prepare children

for life in a digital and highly globalised world.

The project supported by the Visegrad Fund was conceived as a model scenario in which the

integration of cultural, sports, and digital educational elements could be tested, while simultaneously

examining the role of artificial intelligence within this process. The implementation spanned three

months and included both educational and developmental activities within participating residential

childcare institutions and an international meeting that made it possible to verify the functionality

and transferability of the proposed approaches in an intercultural environment.

This study is situated at the intersection of two lines of inquiry: long-term research into

education in residential childcare and a targeted project exploring the potential of cultural, sports,

and educational activities for children in care. In parallel, the study examines innovative pedagogical

strategies that incorporate artificial intelligence. This framework not only allows for the description

of identified educational opportunities. It also outlines a methodology that may serve as a source of

inspiration for further research and practice in this field.

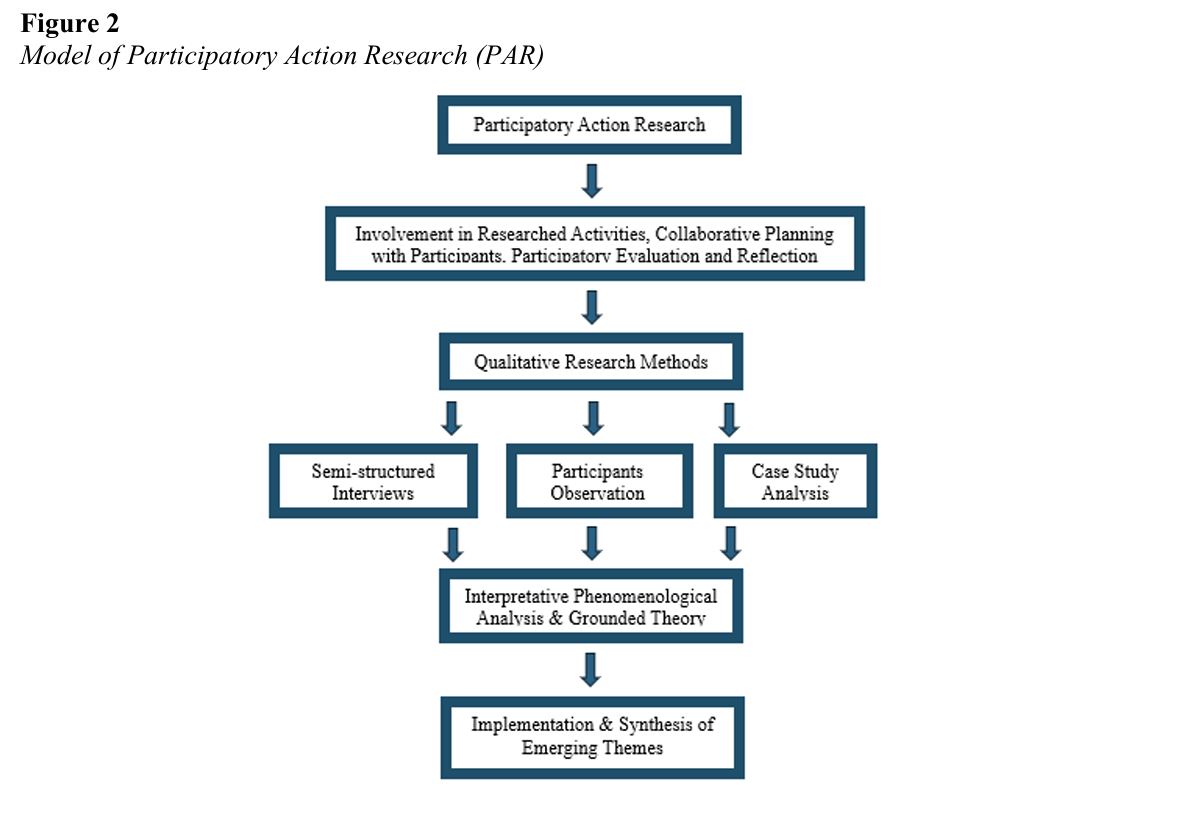

In determining the most appropriate methodological design to achieve the objectives of this

project, we deliberately excluded quantitative methods and opted instead for a qualitative research

model. Given our sustained close engagement with the target population, the most suitable approach

for the present study was Participatory Action Research. The following sections of paper describe

the study group and the context of the examined activities. This is followed by a detailed

presentation of the research instruments, situated within the framework of Participatory Action

Research. Ethical considerations are addressed, and the limitations of the chosen research approach

are critically evaluated.

Research Context

This study was embedded within the international project Sport, Culture, and Education:

Empowering Visegrad’s Children for a Brighter Future, supported by the Visegrad Fund. The

primary fieldwork took place in June 2025 in Zlín, Czech Republic, during a flagship event, the

Visegrad Unity Games. This event was designed to promote social inclusion, intercultural dialogue,

and participatory educational practices for children in residential childcare settings. The programme

brought together participants from the Czech Republic and Slovakia, as well as a unique group of

Ukrainian children temporarily relocated to Poland due to the war. Our study involved 68 children

from Slovakia and the Czech Republic, along with a unique group of 15 children from a Ukrainian

residential childcare facility temporarily relocated to Poland due to the war. These children were

accompanied by 21 childcare professionals, educators, and other specialists.

The Visegrad Unity Games

At the core of the programme were the Visegrad Unity Games. This event was planned as an

integrative sports-based initiative that went far beyond traditional athletic activities. Unity Games

was designed around principles of teamwork, empathy, and intercultural communication. This event

provided a structured yet playful environment in which children could interact across linguistic and

national boundaries. Physical movement served not only to enhance well-being but also to create a

shared symbolic language that supported the development of mutual trust and social cohesion.

Rather than positioning inclusion as an abstract goal, the Visegrad Unity Games offered a space

where inclusion was enacted in real time, through embodied, cooperative experience. In parallel

with the sports programme, two thematic workshops were implemented to promote deeper

educational and cultural reflection.

Visegrad Skills for Inclusion: Empowering through Education

This event focused on the role of education in cultivating key civic and social competencies.

Children engaged in activities promoting metacognition, self-reflection, and peer exchange,

highlighting regional similarities and differences in their educational journeys. Emphasis was placed

on agency, motivation for learning, and the development of soft skills essential for 21st-century

citizenship.

Cultural Mosaic of the Visegrad Nations

This workshop employed creative methods such as drama-in-education, storytelling, and

symbolic art to enable children and staff to share their experiences and co-construct narratives. The

workshop was centred on identity, memory, and community. The aim was to strengthen cultural

self-awareness and foster mutual respect. The workshop builds a sense of belonging within the

diverse cultural landscape of the Visegrad region with the help of cultural activities.

Use of Artificial Intelligence in Participatory Practice

Both workshops incorporated the intense use of artificial intelligence as a supportive

educational and analytical tool. AI applications facilitated personalised content creation, automated

transcription of reflections, and preliminary thematic analysis. Additionally, AI-assisted visual

design enabled the co-creation of artistic outputs by participants. These innovations will be

discussed in more detail in the following sections, where we explore their pedagogical and ethical

implications in depth.

The Zlín event offered a rare opportunity to be part of the process of integration of sport,

culture, and education into a single, cohesive experience. The whole program was tailored to the

specific needs of children in residential care. By creating a holistic and inclusive educational

environment, the event empowered children to engage actively with the concept of inclusion, build

their self-confidence, and experience transnational solidarity in action. The programme thus serves

as a model for participatory and inclusive practices within and beyond the Visegrad region.

Instrument and Procedures

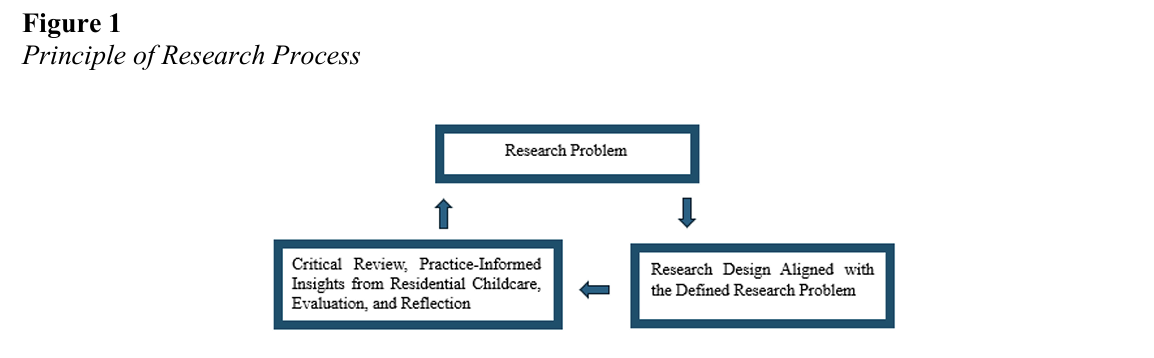

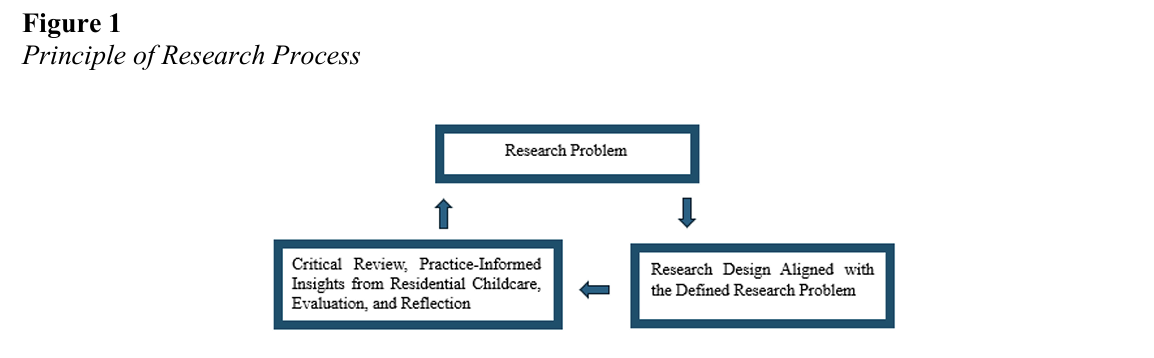

Pedagogical research is, for us, an ongoing and cyclical process, a continuous sequence of

inquiry illustrated in Figure 1. This research cycle begins with the precise identification of the

research problem, grounded in prior studies, professional practice, and consultations with both

subject-matter experts and representatives of the target population. Based on the defined research

problem, an appropriate research design is then selected.

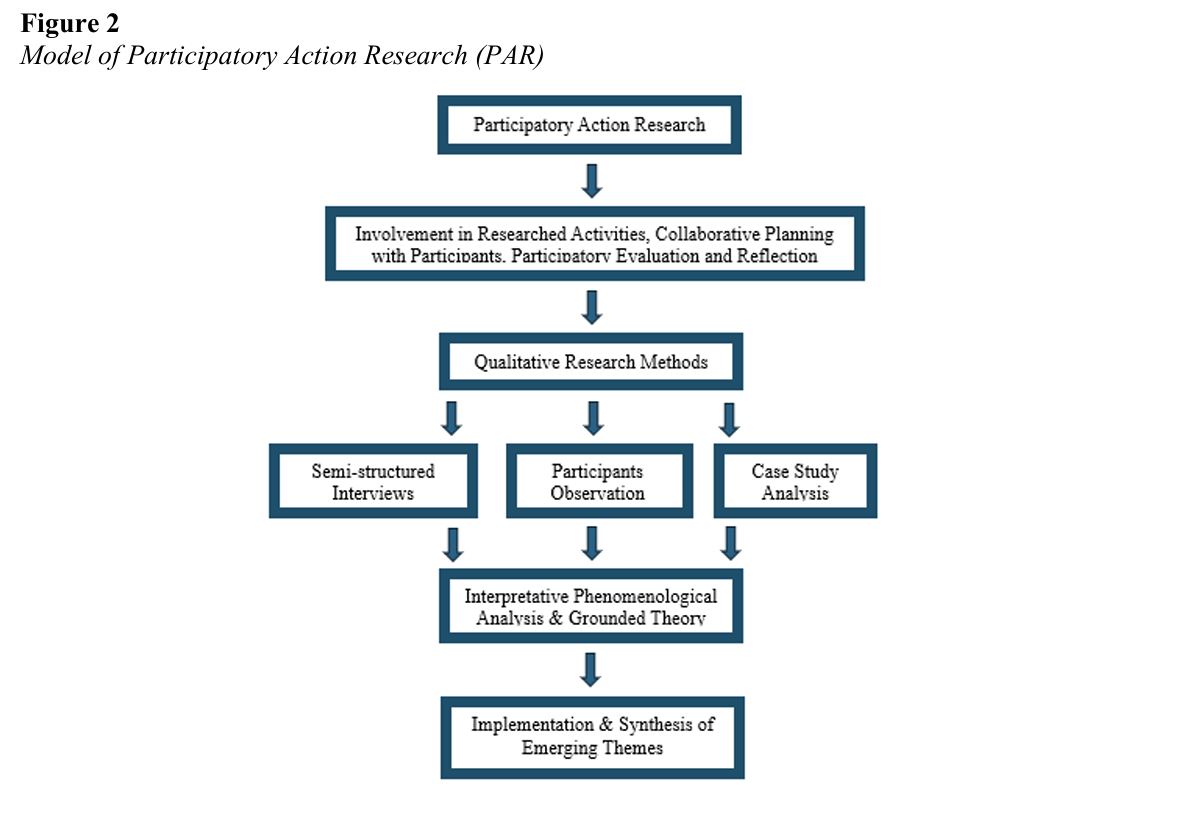

The selection of the methodological framework for the present study stems from the need to

examine educational opportunities within residential childcare, with a particular focus on the role of

cultural, sports, and educational activities, as well as the integration of artificial intelligence into

educational practice. Recognising the necessity of engaging the target group in the research process,

we adopted Participatory Action Research as the guiding framework. Within this framework, we

implemented a systematic process of data collection using qualitative methods, including direct

observation of sport, cultural and educational activities, semi-structured interviews with children and

staff, and group discussions.

The collected data were analysed through the combined use of Grounded Theory and

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis, which together enable an in-depth understanding of

participants’ individual experiences and their positioning within the broader theoretical context of

inclusive education, social pedagogy, and the educational application of modern technologies. The

analytical results were subjected to critical review within the project team, including representatives

of the target group, and further discussed with experts and representatives of participating

institutions to ensure validity and, where necessary, refine the interpretative framework.

Validated findings were subsequently disseminated in the form of reports shared with the

participating institutions and the wider professional community. The main dissemination channel

went through cooperation with FICE Czech Republic. The final stage of the process comprised the

evaluation and reflection on the entire research cycle, assessing the extent to which the objectives

had been achieved and identifying possibilities for further research and practice. These outcomes

informed the formulation of new research questions and initiated the next cycle of Participatory

Action Research. At the end of this research, a new research starting point was created. This cyclical

approach allows for a flexible and adaptive methodology, particularly well suited to the context of

residential childcare, where the conditions and needs of participants may shift rapidly and

significantly.

Participatory Action Research

Participatory Action Research

Participatory Action Research (PAR) represents a methodological approach that links the

process of knowledge creation with purposeful action aimed at fostering change within the

environment in which the research is conducted (Baum, 2006; McIntyre, 2008). It is grounded in a

partnership between researchers and participants. Both parties jointly identify problems, formulate

objectives, engage in data collection and analysis, and interpret the results (Cornish et al., 2023). In

the context of working with children and young people, PAR enables the strengthening of their

voice and active participation in decisions that directly affect them (Shamrova & Cummings, 2017;

Modi, 2020). This approach is regarded ethically and pedagogically beneficial. It provides children

with the opportunity not only to share their experiences but also to contribute to the creation of

solutions that reflect their genuine needs (Flicker, 2008).

PAR is particularly valuable within residential childcare. Children in such settings often face

marginalisation and their perspectives are frequently overlooked in decision-making processes

(Arnadottir et al., 2025; Hoffnung-Assouline et al., 2025). PAR functions not only as a research

method in this context, but also as a tool for fostering competence, building trust, and creating

bridges between children, professionals, and the wider community. Its application with children,

however, requires methodological sensitivity, particularly when working with very young

participants, addressing power imbalances between adults and children, and ensuring meaningful

opportunities for participation (Shamrova & Cummings, 2017).

Recent developments in PAR also emphasise its adaptation to the digital environment. New

technologies can broaden opportunities for participation but simultaneously introduce new

challenges in the areas of digital inclusion, data protection, and the ethics of technology use

(Cockerham, 2024). In the present study, the PAR framework was selected not only because it

allowed for the examination of educational opportunities within residential childcare, but also

because it facilitated the implementation of innovative approaches that directly responded to the

needs and experiences of children.

Interviews and Observations

Observation and interviews represent key qualitative methods. They enable researchers to

gain an in-depth understanding of participants' experiences and the dynamics of interactions within

their natural environment. Observation provides an opportunity to capture a wide range of

phenomenons such a behaviour, non-verbal communication, and contextual nuances that might

otherwise remain hidden. But it is essential to acknowledge its limitations, particularly the potential

influence of the researcher's presence on participants' behaviour and the risk of subjective

interpretation (Boyko, 2013; Sirris et al., 2022). In this study, observation was employed to

systematically monitor the educational, sporting, and cultural activities of children within the

project, with particular attention paid to intercultural interactions and engagement in inclusive

activities.

Qualitative interviews offer access to the personal experiences and internal perspectives of

participants, while also creating a space for the co-construction of meaning between the researcher

and the respondent (Espedal, 2022; Dunwoodie et al., 2023). Conducting compelling interviews

requires the preparation of open, transparent, and context-sensitive questions. Researchers have to

be prepared for active listening, and the ability to respond flexibly to participants' answers (Demirci,

2024). In our research, semi-structured interviews were conducted with both children and

accompanying professionals, with particular emphasis placed on creating a safe and trusting

environment that encouraged openness and the authentic sharing of experiences. The combination of

observation and interviews enabled the collection of a comprehensive picture of the educational

opportunities and needs of children in residential childcare, both from the perspective of the

participants themselves and from that of their caregivers and educators.

Case study

The case study represents a research approach that enables an in-depth and detailed

exploration of a specific phenomenon within its natural context (Hamilton & Corbett-Whittier,

2013; Carter, 2024). In educational research, this method is particularly relevant when the aim is to

understand complex learning processes, account for the interactions among participants, and analyse

the specific conditions under which teaching and learning occur (Grauer, 2012; Shrestha &

Bhattarai, 2021). Critical analyses of its methodology emphasise the necessity of clearly defining

what constitutes a case study and ensuring that the principles of internal validity and transparent

description of the investigated case are upheld (Wohlin & Rainer, 2022).

The case study is especially valuable in the context of inclusive education, because it allows

for the capture of nuances and the complex dynamics of inclusion that might be overlooked in other

research approaches (Shrestha & Bhattarai, 2021). Within the present study, the case study approach

was applied to the unique context of a group of Ukrainian children from residential childcare who

had been evacuated to Poland as a result of the armed conflict. This approach created an opportunity

to analyse how cultural and social factors influence their educational experiences, adaptation, and

participation in inclusive and multicultural educational activities (Takahashi & Araujo, 2019).

Data Analysis

The data analysis in this study combines the approaches of Interpretative Phenomenological

Analysis (IPA) and Grounded Theory (GT), which together enable a deep understanding of

participants’ individual experiences while systematically generating theory grounded in the data.

IPA focuses on a detailed exploration of how individuals perceive and interpret their life

experiences, placing particular emphasis on the depth of meaning and the subjective perspective of

participants (Biggerstaff & Thompson, 2008; Rajasinghe, 2020). This approach is especially

relevant in the context of residential childcare, where it is crucial to understand individual

trajectories, lived experiences, and the ways children adapt to specific life circumstances (Alase,

2017; Van Manen, 2018).

GT complements this by identifying emergent patterns and categories within the data and

integrating them into a broader theoretical framework (Makri & Neely, 2021). This approach is

based on the cyclical process of open, axial, and selective coding, which allows for the gradual

refinement of analytical categories and their systematic linkage to empirical evidence (Charmaz &

Thornberg, 2021). The combination of IPA and GT enables the capture of individual experiences'

uniqueness while generating more generalisable insights that contribute to the theoretical

understanding of educational processes in residential childcare.

Given the cross-cultural nature of the project, the analysis was conducted comparatively to

identify both similarities and differences among groups from different countries. At the same time,

the individual perspective of each child was carefully respected, as experiences could vary

significantly even within the same group, depending on personal history, prior educational

opportunities, and current psychosocial circumstances.

Particular attention was devoted to the interpretation of data from the Ukrainian group. Their

experience of forced displacement and life in exile presented specific challenges and opportunities

for the educational process. Their reflections offered valuable insights into the role of cultural

identity.

Throughout the analytical process, findings were regularly discussed within the research

team and triangulated with the perspectives of educators and professionals from participating

institutions. This participatory validation helped minimise the risk of interpretive bias and ensured

that the resulting themes accurately reflected the lived realities of the participants.

Ethical aspects of research

The research is designed and implemented following international standards for working

with children and young people in sensitive social contexts, and it adheres to the ethical principles of

Participatory Action Research (Correia, 2023; Kiernan & McMahon, 2024). It also incorporates the

principles of value-sensitive design, which require an explicit ethical commitment in the

development of methods and tools, particularly when working with technology (Jacobs &

Huldtgren, 2021). All participating institutions and individuals are fully informed in advance about

the objectives, methods, and intended use of the project’s outcomes. Informed consent is obtained

from both the legal guardians of the children and the children themselves, using formats appropriate

to their age, cognitive abilities, and level of comprehension.

Particular emphasis is placed on protecting participants’ identity and privacy. All data are

anonymised, and photographs or audiovisual recordings are made only with prior informed consent.

No such materials are disclosed without explicit authorisation. Identifiable information is stored

separately from research data and is accessible only to a strictly limited group of authorised

individuals.

Specific ethical risks are carefully addressed when artificial intelligence tools are employed.

The most evident risk areas were especially those related to personal data protection, cultural

sensitivity, and the relevance of generated content. All AI-generated outputs are subject to human

review prior to use or dissemination to participants, in order to prevent the distribution of inaccurate,

inappropriate, or culturally insensitive material.

The principle of minimising the burden on children is consistently applied throughout the

project. Participation in both activities and research is entirely voluntary. Individuals may withdraw

from research at any time without adverse consequences. A safe and supportive environment is

ensured, fostering open engagement without fear of judgement or stigmatisation. Strong adherence

to these ethical principles is essential for ensuring the validity of the research findings. A sound

ethical research approach strengthens participants' trust and supports the long-term sustainability of

collaboration between the researcher, target group and participating institutions.

Limitations of the Study

This study, conducted as part of a long-term investigation into educational opportunities

within residential childcare, employed the framework of participatory action research (PAR) to

integrate research objectives with practical interventions, authentic engagement of children, and the

incorporation of artificial intelligence into both the educational and analytical phases. The target

group comprised delegations from Czech and Slovak residential care institutions and a specific

Ukrainian group evacuated to Poland, with data collected and analysed through qualitative methods

emphasising ethics, intercultural sensitivity, and the validity of findings. Several limitations must be

considered when interpreting the results.

First, the project was implemented over three months and involved a relatively small number

of institutions. Although the sample included diverse institutional settings and national contexts, it

cannot be regarded as fully representative of all forms of residential childcare in the Visegrad

countries.

Second, the experiences of the Ukrainian group, which had been fully evacuated to Poland

due to the war, represent a unique context that is difficult to compare with other participating

groups. These particular circumstances may significantly influence their educational needs and

adaptation processes.

Third, the nature of participatory action research, which combines the roles of researcher and

facilitator, carries a risk of interpretive bias. While this risk was mitigated through ongoing

reflection, team triangulation, and validation of findings with participants and staff, it cannot be

fully eliminated.

Fourth, the use of artificial intelligence tools was piloted on a limited scale and adapted to

the specific needs of the target group. Consequently, findings on the effectiveness of AI in education

within residential childcare settings should be regarded as exploratory and require further

verification on a larger scale and in different contexts.

Finally, it must be acknowledged that the research took place in a dynamic environment

influenced by various external factors, including staff changes, the current legislative framework,

and limited material resources, all of which may affect the implementation and sustainability of the

innovative educational approaches identified in this study.

Research Results

The findings indicate that a comprehensively designed educational process, integrating

learning, sports, and cultural activities, significantly enhances the engagement of children from

residential childcare settings and increases their willingness to learn. This synergy creates a

stimulating environment in which children not only acquire new knowledge and skills but also

strengthen their social bonds, self-confidence, and ability to collaborate.

Throughout the research, the integration of artificial intelligence emerged as a recurring

theme, offering new opportunities for the individualisation and adaptation of educational activities.

The use of AI was not the primary aim of the project but rather a complementary element that

supported an inclusive, child-centred approach.

Owing to the chosen research design, we were able to capture a wide range of noteworthy

findings. The following section presents an overview of the most salient recorded codes, along with

the most compelling statements from both the participating children and the professional staff who

were present during our research activities.

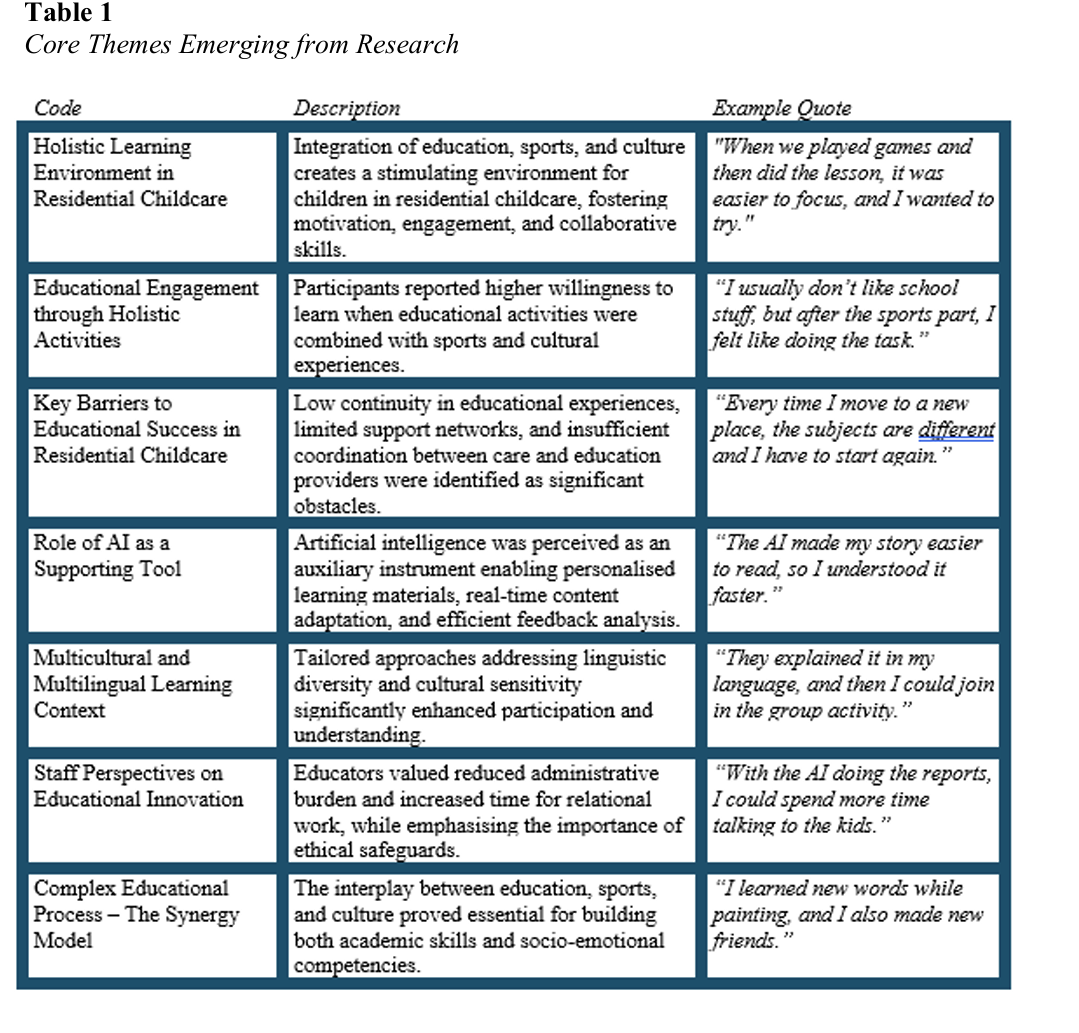

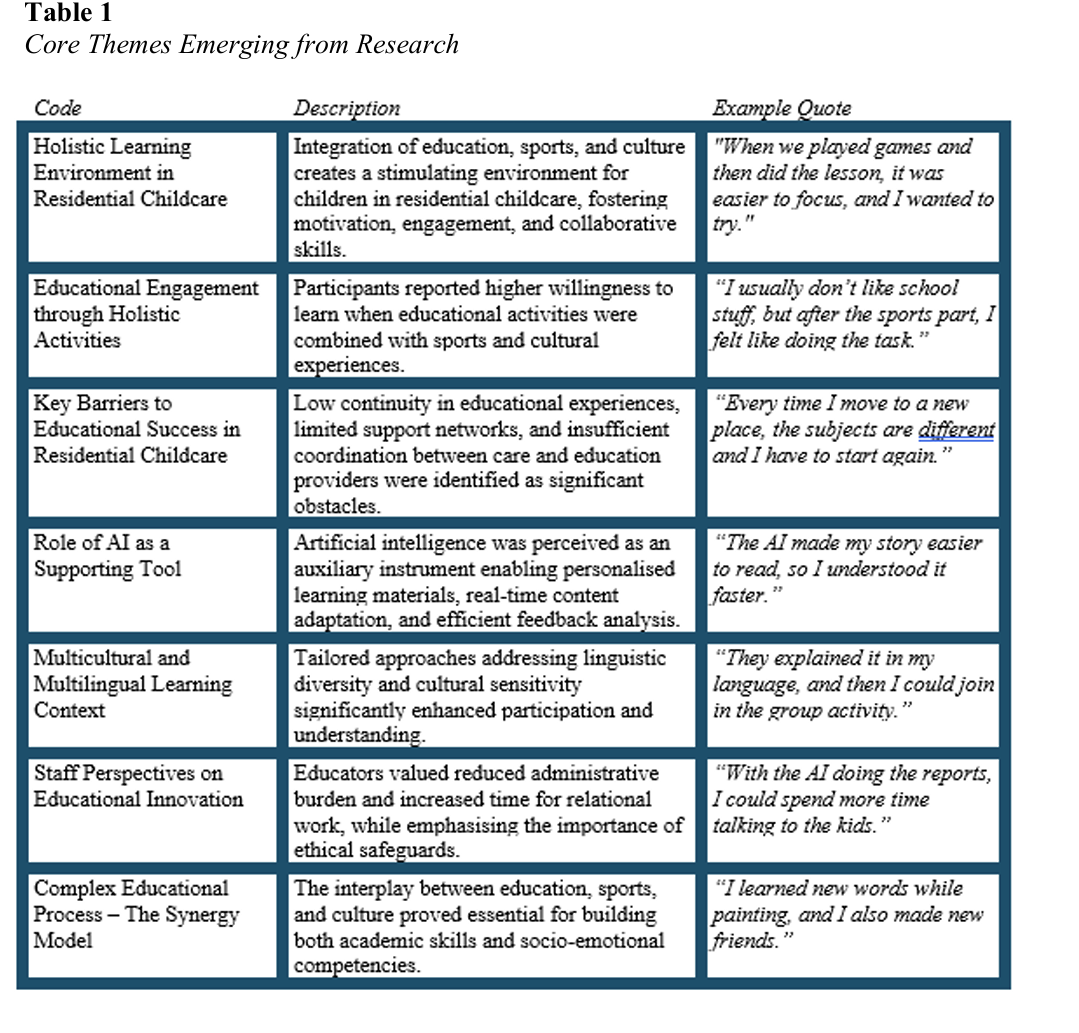

Table 1 summarises the key thematic codes identified through the analysis of qualitative data

collected during the project. Each code reflects a distinct dimension of the educational experience in

residential childcare, capturing both enabling factors and persistent barriers. The explanations clarify

the scope and meaning of each code, while the example quotes, directly drawn from participant

statements, provide authentic insight into the lived experiences of children and staff. The

combination of holistic activities, personalised support, and culturally responsive approaches

emerges as central to fostering motivation, engagement, and socio-emotional development. At the

same time, structural barriers such as limited continuity and coordination remain critical challenges.

The findings of our study reveal that the integration of education, sports, and culture within a

single programme creates a dynamic and motivating learning environment for children in residential

childcare. Participants demonstrated higher willingness to engage in educational activities when

these were embedded in a broader set of experiences, including physical activity and creative

cultural workshops. This multidimensional approach enhanced both cognitive and socio-emotional

development.

One of the key outcomes was the identification of AI as a valuable supporting tool within

this complex educational setting. While not the central focus of the intervention, AI’s role proved

increasingly significant in addressing the diverse and evolving needs of children in residential

childcare. It facilitated the creation of personalised learning materials, adapted content to varying

literacy levels in real time, and supported multilingual communication. Its capacity to rapidly

process qualitative feedback enabled facilitators to make timely, evidence-based adjustments to

activities, thus maintaining high levels of responsiveness to participant needs.

The analysis further indicated that the use of AI contributed to overcoming specific

challenges associated with the fluctuating composition of residential childcare groups, the variability

in educational backgrounds, and the multicultural nature of the participant cohort. AI-supported

adaptations helped sustain continuity in learning despite these contextual shifts, making it a relevant

and necessary tool for an environment characterised by constant change.

At the same time, the results highlight persistent structural barriers to educational success,

including limited support networks and insufficient coordination between care and education

providers. While AI provided valuable operational and pedagogical benefits, it did not replace the

need for strong human facilitation, ethical oversight, and inter-institutional cooperation. The

prevailing finding is that in a dynamic residential childcare environment, AI should be viewed as a

necessary complement to human-led, holistic education rather than as a substitute for it.

Discussion

The findings of this study reinforce the understanding that effective education in residential

childcare must be approached as a complex, multidimensional process. The integration of education,

sports, and culture within a unified programme created a stimulating environment that not only

improved cognitive engagement but also strengthened socio-emotional skills and collaborative

competencies among participants. This synergy supported the intrinsic motivation of children to

participate in learning activities, even among those who had previously shown limited interest in

formal education. Education, in this sense, serves as a bridge to a better future—one that is not

limited to the acquisition of knowledge but extends to the development of competencies essential for

full participation in society. For children in residential care, this bridge can be transformative,

offering opportunities to overcome structural barriers and expand their life prospects.

A central insight emerging from the research is the growing necessity of artificial

intelligence as a supportive element in such a dynamic educational context. Although AI was not the

primary focus of the intervention, its adaptability proved crucial in responding to the diverse,

multilingual, and often fluid nature of residential childcare groups. Personalised content generation,

rapid adaptation to differing literacy levels, and the facilitation of culturally sensitive

communication significantly reduced barriers to participation. In addition, AI-enabled real-time

analysis of qualitative feedback allowed facilitators to refine activities almost immediately, ensuring

that programmes remained responsive to children’s evolving needs.

However, the study also highlights the importance of maintaining human-centred practices

alongside AI deployment. While AI contributed to efficiency, inclusivity, and continuity in

education, it cannot replace the relational, ethical, and contextually informed judgment of educators.

The risk of over-reliance on automated processes remains a valid concern, particularly in the context

of vulnerable children, where trust-building and emotional safety are paramount.

These findings suggest several directions for future research. Longitudinal studies are needed

to assess the sustained impact of holistic, AI-supported educational programmes in residential

childcare. Further exploration of culturally adaptive AI models could enhance linguistic and socio

emotional sensitivity, especially in post-conflict or migration-affected contexts. Moreover,

comparative studies between AI-assisted and traditional approaches could clarify the extent to which

technological tools contribute to long-term educational and developmental outcomes. In this regard,

our research team has already initiated an experimental study testing AI-assisted design of

educational programmes for children from Muslim countries, whose representation in residential

care in Central Europe has increased in recent years. This follow-up work aims to assess whether AI

can facilitate the creation of personalised, culturally responsive interventions and further strengthen

education’s role as a driver of social inclusion.

Conclusions and Implications

The present study confirms that education in residential childcare cannot be effectively

delivered through isolated interventions or single-domain activities. It must be understood as a

holistic and multi-layered process in which education, sports and culture interact synergistically to

create a stimulating and inclusive environment. This integrated approach supports cognitive growth

and academic achievement while also cultivating socio-emotional skills, intercultural understanding

and the capacity for collaborative problem solving. These competencies are essential for children’s

long-term social integration.

A significant outcome of the study is the positive shift in children’s intrinsic motivation to

learn when educational activities are combined with cultural and physical components. Even

participants with previously limited engagement in formal education demonstrated greater

willingness to participate. This suggests that a balanced combination of intellectual, physical and

creative stimuli can break down long-standing barriers to learning in care settings.

Although artificial intelligence was not the primary focus of the programme, its emerging

role as an adaptive support tool was evident throughout the project. AI-enabled content

personalisation, multilingual communication and real-time feedback analysis proved essential in

responding to the dynamic and diverse composition of residential childcare groups. This adaptability

allowed facilitators to tailor materials to varying literacy levels, cultural contexts and individual

needs, reinforcing inclusivity and efficiency. AI also enhanced the responsiveness of programme

design by enabling the rapid incorporation of participants’ feedback into subsequent activities.

The findings also make it clear that artificial intelligence cannot replace the relational,

ethical and contextually informed role of human educators. The trust, empathy and professional

judgement required in working with vulnerable children remain beyond the capacity of current

technological tools. The challenge for the future is to use the strengths of AI in adaptability,

efficiency and data processing while safeguarding the human-centred principles that are

foundational to effective education in care environments.

The results point toward several important directions for further research and practice.

Longitudinal studies should examine the sustained impact of holistic AI-supported interventions on

educational and developmental trajectories in residential childcare. Comparative analyses between

AI-enhanced and traditional pedagogical approaches could provide clearer insights into the value of

technology in this context. Given the increasing cultural diversity in care settings, including the

growing number of children from Muslim-majority countries in Central Europe, future projects

should focus on developing and testing culturally adaptive AI models to support tailored educational

programming in migration-affected contexts.

This research positions holistic AI-informed education as a promising avenue for expanding

the accessibility, quality and relevance of learning opportunities for children in residential care.

Embedding technology within a framework that integrates education, sports, and culture can

enhance immediate learning outcomes and lay the foundations for lifelong competencies that

empower children to participate fully and confidently in society.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on outcomes from the project Sport, Culture, and Education: Empowering

Visegrad's Children for a Brighter Future, project ID #22510218. The project was co-financed by

the governments of Czechia, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia through Visegrad Grants from the

International Visegrad Fund. The mission of the Fund is to advance ideas for sustainable regional

cooperation in Central Europe. We gratefully acknowledge the generous support of the Fund,

without which this inclusive cross-border initiative would not have been possible. We would also

like to express our sincere gratitude to the Federation of Children’s Homes FICE Czech Republic

and, above all, to all the children who took part in the project for their enthusiasm, commitment, and

invaluable contribution.

References - please donwoload the PDF file of the Article.

Download file

Participatory Action Research

Participatory Action Research